How to survive and thrive in uncertainty: 4 lessons from Die Hard

Welcome to product management, pal

So much of being a product manager is getting comfortable in the face of uncertainty, the state in which you have limited knowledge and so cannot, with total accuracy, describe current or future circumstances. Discovery is especially messy and nonlinear, but even when we’re in Delivery we spend a lot of time trying to understand what we don’t yet know. It’s never a sure thing that the opportunity we’re looking to solve, or the way we’re thinking of solving it, will be one that is most valuable for our customers and our business – or that our stakeholders will come on every step of the journey with us.

But there are ways we can manage that aspect of product management better. Here are four of them, as taught to us by Die Hard.

1. Continually evolve your understanding of the problem space

When a group of terrorists descend on Nakatomi Plaza, John McClane manages to get away and remains uncaptured. But instead of finding a cosy place to hide, he finds the floor they’ve taken executive, Joseph Takagi to and listens in to understand who they are and why they’ve turned up to create so much pain. McClane uses his growing knowledge to inform the police outside and to make decisions when he encounters risks.

“How does he know so much about us?”

- Terrorist’s comment after McClane first makes face-to-face contact

Even though McClane is running around a building trying not to get killed, he is still tracking as much information as possible. For example, by keeping a list of the terrorists’ names on his arm. While you’ll clearly have more opportunities and resources with which to track your findings, make sure you do so. One of the best ways to make sure you’re getting a complete picture of the problem you’re solving is to track it in a Product 1-Pager (some might call this a PRD, or Product Requirements Document). Keep it short and concise.

What should a 1-Pager include? The precise contents will depend on the context, but at a high level you’ll want to have:

The names of important points for contact, i.e. authors who contributed to the document/ the product trio

The goal of the product, e.g. your North Star metric

A description of the problem (1-2 sentences). This should include why it’s important to customers and the business, and evidence that supports this

A description of the solution, which could include features, key flows, or product, design, and technical specs.

Lenny Rachitsky has collected his favourite templates from around the internet here (paywall). They make great starting points to adapt to your product and team’s needs, so that everyone can align quickly on what you’re setting out to achieve.

2. Admit what you don't know

“In order to learn, you need to first admit ignorance.”

John McClane is an everyman who was literally caught without shoes on, drawing attention to how susceptible he is to being hurt. His ability to admit what he’s not sure about means he has a vulnerability that is relatable and endearing. In an action movie setting, this makes him a different kind of hero. In a work setting, we can use this as a reminder that being honest about what we don’t know allows us to both learn and build relationships.

“I don’t know what it means, but we’ve got some badass perpetrators and they’re here to stay.”

John McClane

Despite McClane’s ten years of experience as a police officer, he’s found himself in a completely new situation. But by connecting with Sergeant Al Powell over radio, he finds external support. As McClane opens up to him, they build a relationship of trust and help one another, both on a personal level and practically. Sergeant Powell has – literally – a different perspective, and this is hugely beneficial for them both. As product managers, we are also often applying our skills in new situations where we may be learning about new industries, products, and customers for the first time, and should be making the most of other views.

One of the most beneficial ways of growing in your career is getting help from your Product peers. Because product is so varied, no one can ever know everything about the discipline. It is a sign of strength to reach out to others to ask questions and get yourself unstuck. At Kin + Carta (where I work), our managers are more like coaches and therefore provide a built-in opportunity to ask for help or advice. We work together as a Practice to share ideas, ask questions, and teach one another new skills. That’s true regardless of seniority – no matter who you are, there’s always more to learn.

3. Keep track of your assumptions

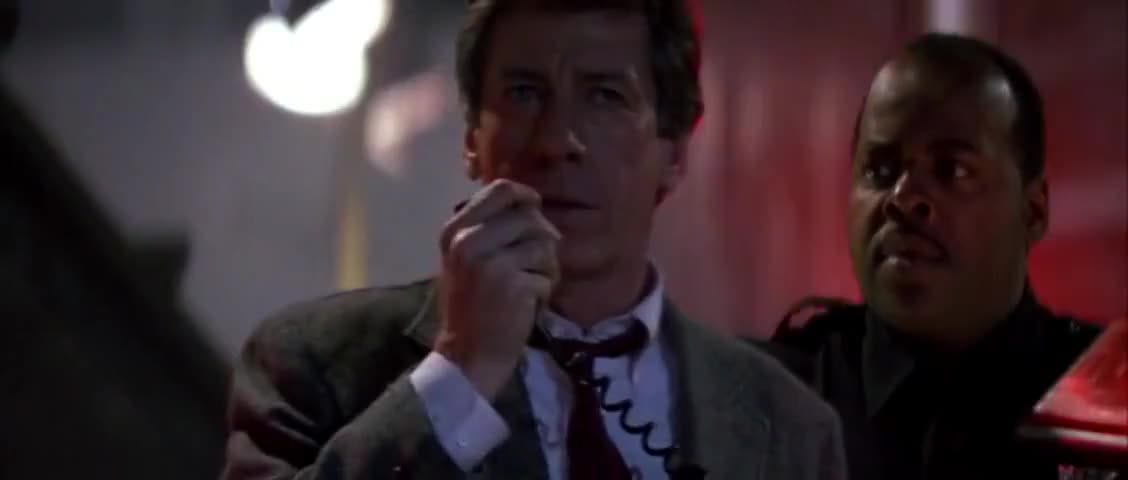

On the other hand, Deputy Dwayne Robinson gets his sense of authority from appearing to know everything, and makes decisions based on his assumptions. He derides Sergeant Powell for trusting “Roy” (John McClane’s alias) based on a hunch, while deciding to send in a SWAT team based on a number of assumptions he hasn’t thought through, let alone determined which is riskiest.

So how do we go about tracking our assumptions?

If you have story mapped your solution, you can use that as a starting point to list the assumptions you need to be true in order for the user to get the value from your solution in the way you intend. Underneath each step of the story map, list these out on sticky notes. It’s often helpful to categorise them, e.g. assumptions you’re making about the desirability, usability, feasibility, or the ethical nature of the solution.

Once you’ve listed these out, plot them on a 2x2 matrix, where the X axis represents the evidence you have in support of your assumption (where a lot of evidence is on the left, and little evidence is on the right), and the Y axis represents how important it is to the success of your solution that each assumption is true (where the bottom is not important and the top is very important). You are then left with your assumptions in priority order, with the highest priority assumptions in the top right corner.

You can also plot out assumptions on other artefacts, for example journey maps or architecture diagrams, and then prioritise them in a similar way.

4. Grow your Circle of Influence with Integrity

“It is inspiring to realize that in choosing our response to circumstance, we powerfully affect our circumstance. When we change our part of the chemical formula, we change the nature of the results.”

- Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

As product managers, there are things we can control and a whole host of things we cannot. All of us have a number of things we think about each day – our relationship with stakeholders, the dependencies we have on other teams, whether our organisation has adopted agile methodologies or not, not to mention things that are occurring outside of work, such our personal relationships, climate change, new government policies, our evening and weekend plans, and so on. The things we can control exist within our Circle of Influence, and when we focus our energies there, we adopt a proactive focus. When we focus our energies outside of our Circle of Influence, we are actually addressing our Circle of Concern and adopting a reactive focus.

Harry Ellis is a smarmy businessman who is used to charming and lying his way through negotiations and relationships. He is proactive, attempting to use other people to help him expand his Circle of Influence, but in doing so he makes a judgment call in assuming that John McClane will maintain his lie and abide by his wishes if Ellis’s life is on the line. McClane, however, knows more than Ellis, and therefore can’t be influenced in this way. Because Ellis chooses to apply his energy dishonestly and without doing the groundwork to understand whether his actions will have the intended outcomes, it does not work out well for him in the end.

The difference is knowing what you can have no, indirect, or direct control over, and choosing how much energy and time to spend on each – and doing so with integrity. Being able to step back, assess our situation, and decide how we’re going to respond ultimately means we positively affect that situation.

You want to know the secret to surviving product management?

When you get to where you’re going, take off your shoes and socks and make fists with your toes, and get ready to face whatever uncertainty comes next.

Great article, Harriet.

You could also argue that, smart as he is, Hans Gruber is defeated because his complex, Waterfall plan can’t respond faster enough to McClane, his agile competitor.