Don’t Cave to Conway’s Law

Stop letting your org chart design your product

Conway’s law states that organisations commonly design systems that mirror their own communication structures. We see this in software development, where the way your teams collaborate has huge influence on how you build - and, in turn, the experience you create for your users.

“Any organization that designs a system (broadly defined) will produce a design that mirrors the organization’s communication structure.”

Melvin E. Conway, 1968

It’s rarely realistic to rip up your company’s organisational structure and start again before you deploy a piece of code. So, how can you work with suboptimal org shapes and still produce brilliant user experiences?

Spot the warning signs

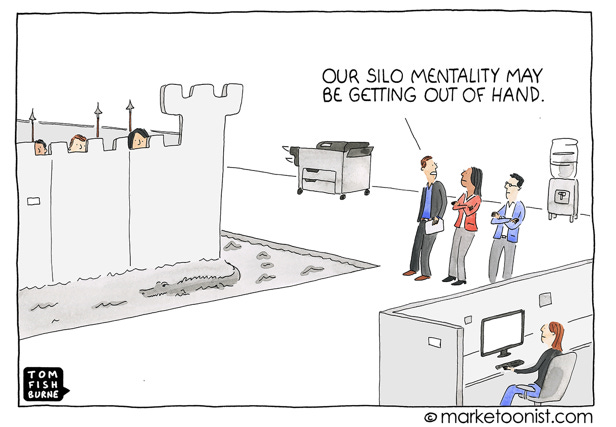

It’s usually clear when you’re working in a poorly designed organisation that could feel the pain of Conway’s Law. Perhaps you’re set up in ‘functions’ such as IT, Finance and Marketing, and you infrequently work with other functions. Maybe your company has an outsourcing model where they contract different parts of a system (e.g. front-end, integration, APIs) to separate, at times competing, third parties.

It all boils down to a common characteristic: your user and their needs are not at the centre of conversations in your organisation. Instead, you spend more time talking about which team is responsible for what. Teams work towards their own, independent goals, and shared, user-focused outcomes are lost.

We have all experienced the negative impact of Conway’s Law in our everyday lives. It’s why you have to repeatedly give the same personal information to public services run by different government departments. It’s why the online experience of traditional banks used to feel like a series of separate company web pages taped together. It’s the reason for those enraging customer service phone calls where you’re passed round and round between different divisions to have a simple question answered.

Bad for users, bad for business

The result for both business and users can be disastrous.

Firstly, it produces a suboptimal user experience that feels like it’s been taped together at random, or where the user gets frustrated because they’re repeatedly providing the same information to different parts of your service. It risks cost and potential incidents because you build systems that are more complex than they need to be, thanks to multiple, misaligned technical strategies playing out in your product.

It’s also massively inefficient. It takes more time to align teams around outcomes, share information and work through issues when you have more people working to opposing incentives. It’s a huge administrative overhead to coordinate independently moving arms to deliver as one.

This is why successful technology companies set themselves up differently. They want to make it as easy as possible for teams to collaborate on creating great products.

What’s a girl to do?

Most traditional organisations don’t have the time or money to shift to a Spotify squad model before delivering their next digital product. So here are some ways you can combat Conway’s Law without radically changing how your teams are set up.

Know your users

Possibly one of the most common tropes in modern product development, but for a reason. Ensuring that everyone involved in your project has a shared understanding of who your users are and the problems you’re solving for them is a fundamental starting point for building good experiences. Ensuring that this view of the user is consistent across siloed teams is key to creating a sense of unity and collaboration, even when org structures don’t support it.

Practical tools: regular user interviews, personas that are easy to reference, shared playback sessions.

Set priorities based on user outcomes

Misaligned incentives are the most flammable fuel to the hellfire of siloed teams. Planning and managing work around user outcomes are one way to create shared incentives instead. Rather than ‘back-end deliver xxx and front-end deliver yyy’, the goal becomes ‘a user can check-out and pay’ and the back-end and front-end teams work together to break down what that means. This requires strong collaboration between potentially disparate parties, which leads us to the next point.

Practical tools: OKRs, shared goals and metrics, shared mission memos.

Facilitate your way to cross-functional alignment

Collaboration between disciplines is the essence of effective software delivery. Where you have siloed, separate teams, achieving meaningful collaboration is hard. You need to actively make it happen through sessions run by experienced facilitators. Session content can be anything from joint planning to solution design and progress tracking. The key is having an impartial facilitator who can bridge siloes and encourage productive contributions. You also need to make sure the relevant people are present for collaboration sessions, to avoid hand-offs and waste later.

Practical tools: agile ceremonies, especially retrospectives, shared roadmaps, co-design workshops.

Appoint a single leadership-level product trio

Product trios (usually made up of a product manager, technical lead and designer) are the decision-making engines of effective teams. If your organisation is building a product through the efforts of multiple disparate teams, it’s essential to place a strong product trio in a leadership position, where they can look across teams to make final calls about prioritisation, technical approach and user experience. A single product, tech and design voice is how you protect against feature bloat and your product feeling like multiple confusing and separate experiences.

Practical tools: three amigos ceremonies, decision logs, shared technical, product and design strategy docs.

Promote transparency and trust

Finally, if your org structure doesn’t naturally promote sharing and collaboration, you can achieve it by creating a culture where transparency and trust are the status quo. This means encouraging teams to share their work and plans, even when (especially when) they’re stuck or don’t have confidence in them. It means enforcing a no-blame culture, where failures are opportunities to learn rather than things to hide. Without this openness, it’s very hard to achieve the collaboration required to build great products. An open approach needs to be role-modelled from the top down as well as practiced from the bottom-up.

Practical tools: demos, show and tells, week notes.

Your fate doesn’t have to be your destiny

Conway’s Law is undeniable, but there are ways to combat it. It takes active, persistent and self-scrutinising actions. But it’s worth the effort if you want to build experiences that delight users and achieve results for your business.

Glad to see someone writing about this. This is a curse which nobody realises. I'll be writing about this soon.